There’s been lots more coverage recently of “WiFi” Radios; radios which stream via the Internet rather than picking up a broadcast signal (FM/AM/DAB). Consumers seem to be enthusiastic about them, and media coverage reflects that enthusiasm.

As it seems impossible for anyone in media to avoid making comparisons, often there’s a line somewhere in the article about DAB being “in trouble”, and that “experts are predicting that internet streaming will over take DAB”.

That would be a disaster for the radio industry, and one that’s avoidable. But more on that in a second.

It’s understandable that consumers are enthusiastic about IP-connected radios. It would appear that consumers are highly motivated to seek out choice in their radio listening, which suggests that they’re not getting that choice now. It’s also pretty clear that regardless of whatever leaps forward in technology occur, people like listening to radio on devices, not on computers. They want something radio-like, and aren’t yet ready to converge on a single-handheld media device.

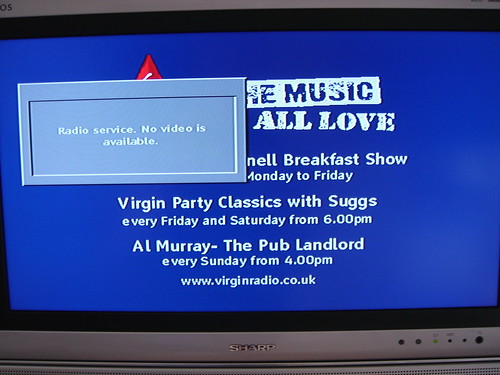

DAB has delivered that choice in the past, but for a variety of complex reasons, stations have come off the platform, leaving it offering little differentiation against analogue. So if consumers are disappointed by choice on analogue, they’re unlikely to be thrilled by turning on their new DAB radio. That’s something the radio industry could fix, but the barriers at the moment are largely commercial and contractual, as well as a bit of ideology as well.

So if IP-connected devices offer the choice that consumers apparently want, isn’t it the future we should promote?

Firstly, let’s check in on that assumption of choice. We know, even in the analogue domain, that much of it is perception. Media platforms are often promoted and compared on a straight “number of channels” basis; only recently has the relatively saturated market of multi-channel TV opened up a new front on “quality” with the promotion of HD. (I find it ironic that DAB went the other way around – maybe we’ll come full circle with high-quality audio once again becoming something to attract mass-market consumers rather than just connoisseurs?). But even with this amazing choice, consumers tend to gravitate towards a small number of stations. RAJAR tells us that the average listener listens to about 3.2 stations a week, roughly 25% of what’s available to them in the typical British city. The growth in number of commercial radio stations in the last decade (many of which now seem to be unsustainable) hasn’t grown commercial market share, time spent listening, nor particularly the total stations listened to figure. So it would appear that so far choice hasn’t grown listening, and therefore hasn’t grown the total revenue coming to the radio industry.

But how much choice do consumers need, and how must does it cost?

Here’s where it gets dangerous for existing radio companies. Offer too little choice (on FM/AM/DAB) and consumers will seek out the IP-connected alternative. Once they have a IP-connected radio, we have to be on it. Allow that platform to grow too much, and we’ve got a cost and competition headache that will make whatever issues with DAB look trivial. As a defence (and referring to the eponymous “long tail model”) it should be able to produce reasonable choice at low-cost on DAB, which might be sufficient to keep the demand for IP services in check.

If IP is the future, why have no existing broadcasters committed to it as their sole digital platform?

The difference between the “experts” quoted in the media and the established broadcasters is knowledge. Broadcasters have the current and forecast data on their audience sizes, the infrastructure costs for supporting that listening on IP, and the existing relationships with the IP networks. When you start modelling costs, they are breathtaking. The radio industry might end up spending ten times more on transmission than it does now. For a small start-up like Last.fm or Pandora (and yes, they are small), having 50-60% of their costs as distribution is probably OK. But for the mainstream, it would be suicide. You also have to consider the effects of introducing to the picture a whole new array of gatekeepers sitting between broadcasters and listeners, looking to make some money. Net Neutrality is going to be a real battle ground in the future.

(At this point, the “experts” usually start going on about multicast solutions and so on. As far as I’m aware, multicast has been technically possible for 10 years. But the reality is that it is so fiendishly difficult to implement multi-cast AND Quality of Service as a pair, across diverse networks, knowing that every single intermediate router needs to properly support both, nobody is seriously considering it on the public Internet).

If the detailed numbers on current streaming volumes were published, people would be staggered. “Experts” would look rather silly. RAJAR gives us a hint now, saying that only 2% of listening is streamed – that’s about 20m hours a week. And most of that is to the BBC. Despite 60% availability of broadband in homes and offices, internet streaming is still tiny. But the widespread perception, even in the radio industry, is that IP streaming is bigger than DAB.

The radio industry needs to avoid IP streaming becoming the sole standard for accessing radio.

The costs of IP would make the mass-market radio model economically impossibly; doubly so in the mobile space. The growth in IP-connected devices would help new entrants like last.fm and Pandora reach the mass-market at speed, and further erode time spent listening. Consumers would end up paying to listen to radio, either directly or indirectly. Maybe that is the future, maybe that’s what people want. But should we accelerate it by forcing consumers into the IP domain to get choice?

IP is an ideal technology partner for broadcast radio.

“Experts” seem to love pitching technologies against each other. IP is better than DAB. WiMax will trump everything. DVB-H will create world peace and bring fresh-water to the thirsty. Etc. They seem to think that one technology will eventually do everything, making all others irrelevant. But I don’t see them advising the use of a 2kg hammer to put a screw into timber.

IP is a great technology for radio if it’s used for what it’s best at. Let’s use IP for delivering personalised advertising, capturing interest in things people hear on the radio, lightweight mobile interaction, on-demand, super-niche and personalised audio services. Broadcast (DAB) is excellent for the heavy lifting, delivering masses of streams reliably and in a timely manner, across wide areas at low costs (both for broadcasters and consumers). The two are complimentary, like screwdrivers and hammers. You need both in your toolkit. We need converged radios, not IP-only radios.

The radio industry should avoid getting trapped in a world where consumers expect radio solely via IP. It’s in our power to incentivise people to buy radios that support an intelligent convergence of broadcast and IP, and not IP alone. The economic incentive for existing radio broadcasters is survival. It doesn’t get clearer than that.

All opinions are my own personal ones, which may differ from those of my employer. Photo is (CC) Geranium at flickr. Oh, and Merry Christmas too.